After studying and working in television in Canada, Amy Doherty returned home to her native Perth only to find there wasn’t much TV work to go around.

Instead, she switched her focus to virtual reality projects. There was one issue: she didn’t know how use game engines or speak the technical language of programmers. Writing things out didn’t help much; it was hard to convey timing, the depths of the interactive worlds or non-linear storylines on the page.

“When I tried to show people, ‘This is what I’m planning, or this is what I’d like to do for this virtual reality experience’, I struggled. One time I even had a paper diorama that I was showing them and moving about, just so we could be on the same page,” she says.

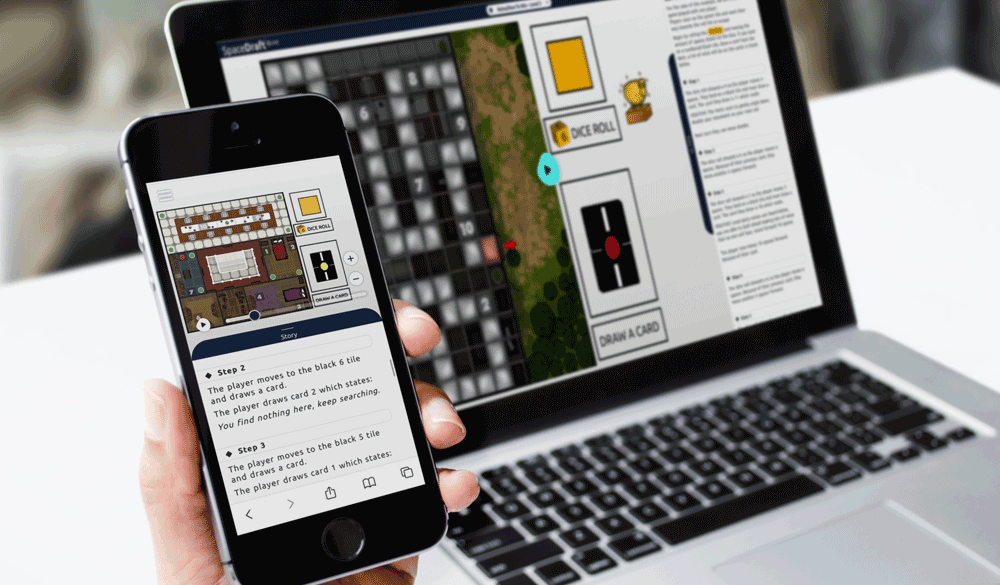

Doherty first heard about SpaceDraft, an Australian cloud-based visual planning platform, at mixed reality conference XR:WA. It was a simple and intuitive tool, incorporating text, sound, graphics and images, that could be easily shared.

She thought SpaceDraft could help in the initial design of VR games, and seemed a lot faster to learn than teaching herself how to use a game engine.

Immediately she found it a simpler way to communicate her ideas around journey, atmosphere and tone with collaborators and funders.

“One of the games I wanted to add narrative to; cut scenes or cinematic moments. I’d written a script and I thought, ‘Well, to get this over the line, why don’t I take the art that they already have and show them how it could work; add a little bit of animation, and show them the timing and the tone’. They were blown away. It’s basically pre-visualisation that they could share and comment on. They had a much better sense of what we were going for.”

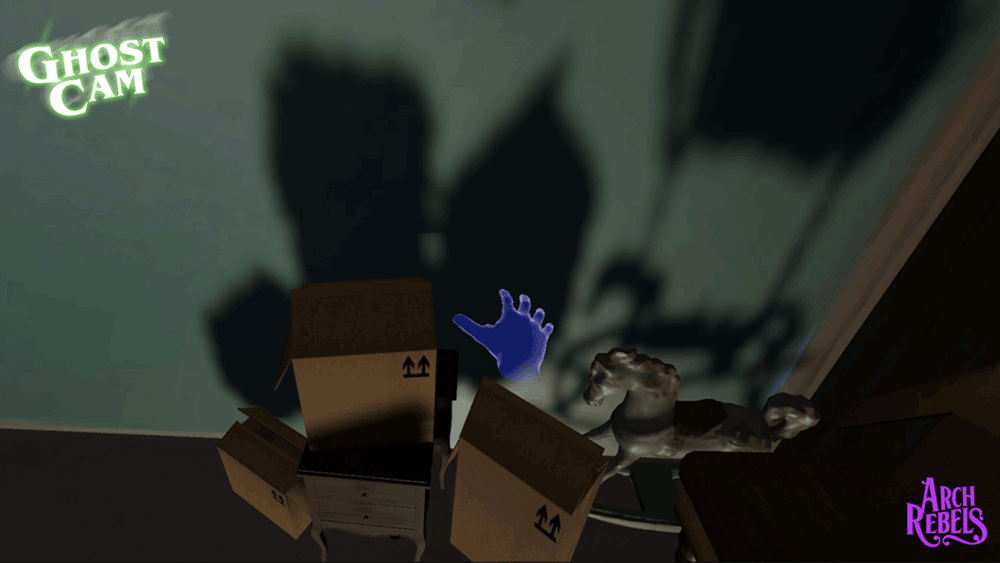

Doherty has used SpaceDraft now in designing several games, including in the tutorial for her project Ghost Cam. As a “non-technical person” it has been “empowering” to use, and allowed her projects to progress more quickly.

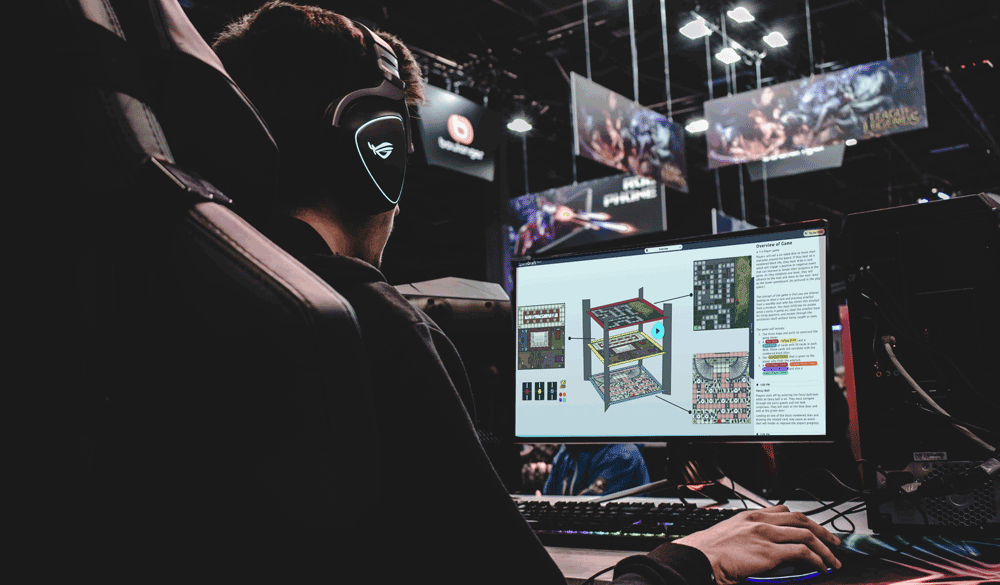

SAE Institute games lecturer Fae Daunt agrees that SpaceDraft is a powerful tool for building prototypes. She’s introduced the software into the classroom with her students as a more intuitive way for them to explain their ideas, particularly around design elements, gameplay and time passing.

“Our early classes involve a board game design module, and in it students need to be able to pitch and communicate an idea they have for a game. If you have ever played a board game before, you know that all the rules in the world don’t really give you a proper understanding of the game until you play it, and SpaceDraft lets them do that,” she says.

“Using the timeline features they can quickly mockup a full visual of what playing the game looks like while they tell us the rules of the game, which syncs those aspects of design and communication that we had trouble with before.”

Beyond the classroom, Daunt also easily sees how SpaceDraft could be used in professional practice, including even as a pitching tool in seeking pre-production funding.

“The visualisation aspect allows easy moodboarding combined with the communication aspects that the timeline offers. In a rapid prototyping environment it allows a team to quickly get across an idea before diving into greyboxing out a concept,” she says.

“SpaceDraft’s visual communication just puts above and beyond what the written word can get across. While documentation can cover everything SpaceDraft does, it does so with industry terminology and understanding. Terms like ‘Coyote time’ – when in a game players can jump just a little after they leave a ledge, named after Wile E. Coyote’s tendency to hang in space after the ground is knocked out from under him – can be written out in great detail, but a visual representation can cover that in detail including how long they should be able to hang for and what animations may be required.”

Having come from a film and TV background, Doherty believes SpaceDraft could be a useful bridge for people looking at moving into games or interactive media who don’t know how to code.

“Not knowing how to use some of this technology, it is a barrier to entry. Virtual reality, and this new stage of this interactive immersive technology, AR, mixed reality – we need creatives and people from different industries and different perspectives to bring the next stage of amazing projects and a reason ‘why’ for some of these platforms to exist.

“It’s like how Hollywood took off in the Golden Age. You had a lot of immigrants coming from different countries who were composers, who worked in orchestras, artists; they came together to create motion pictures. People from different industries, different backgrounds. The same thing needs to happen for virtual reality, games and immersive. It is happening already, but I think it’s easier when you can communicate what your ideas are, what you can offer or what your vision is.”

This article is from IF Magazine (16 September 2022), “Want to visualise a game idea but don’t know how to code?“.